2012-10-08 / The Work Department

In our recent blog post about messaging, we introduced our “meshaging” (basic chat) application and explained some of the plans for our future work with it. We are still working on this project and have diagrammed how exactly communication happens in the application. This has improved our internal process and we think it's beneficial to share.

Compared to centralized, server-based systems, decentralized networking applications are a bit messy: with the benefit of decentralization comes the cost of increased complexity. Maintaining consistency of data across a mesh network is a hard problem to solve, and there are plenty of interesting approaches to address this problem. As designers, we became interested in embracing inconsistency: what systems could exist, or even thrive, in a network of inconsistent connections or transient devices? This is important to consider because a mesh network could be constantly changing.

To explore the subject of decentralized communication, we decided to work through the design of a mesh network chat application in which nodes would serve as chat hubs. We considered what a decentralized chat application would look like with varying levels of message-sharing or replication between neighbor nodes.

We used the analogy of a chat application because of its simplicity and its generality, but you can replace “chats” with any sort of one-to-many message. Actually, as an exercise, you really should try and think of other types of messages that might be transported over a mesh network! Imagine a network of thermometers in a greenhouse, or a network of motion sensors that trigger floodlights, or many other possibilities.

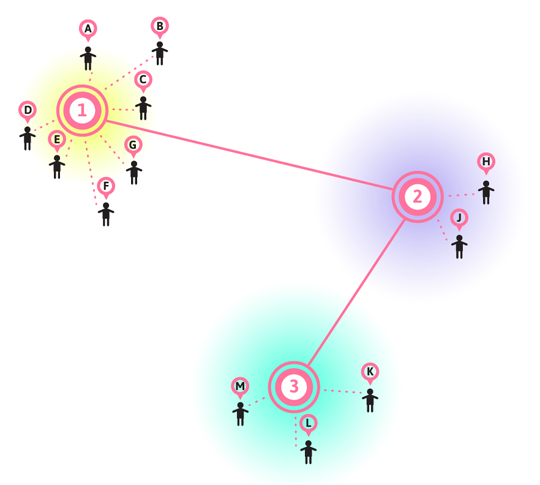

Diagram 1 (above) illustrates a chat application in which nodes broadcast messages only to locally connected clients (zero hops). The numbers 1, 2, and 3 represent nodes connected to the mesh network, and the little people icons designated with letters represent the people connected to each of those nodes. In this scenario, users can chat with other users on the same node. For example, Person H can chat with Person J because they are both connected to Node 2. They cannot however chat with Person K or Person D, because those users, though connected to the mesh network, are on different nodes.

Diagram 1 (above) illustrates a chat application in which nodes broadcast messages only to locally connected clients (zero hops). The numbers 1, 2, and 3 represent nodes connected to the mesh network, and the little people icons designated with letters represent the people connected to each of those nodes. In this scenario, users can chat with other users on the same node. For example, Person H can chat with Person J because they are both connected to Node 2. They cannot however chat with Person K or Person D, because those users, though connected to the mesh network, are on different nodes.

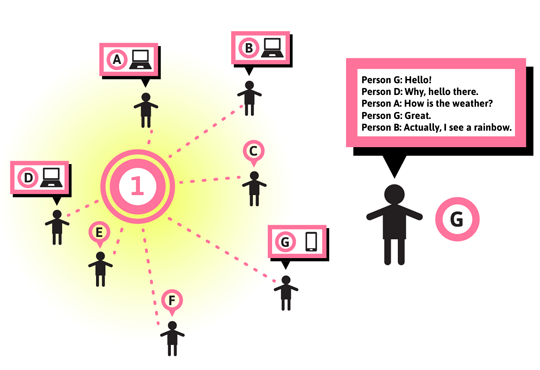

Diagram 2 **(above) illustrates users on Node 1 communicating (zero-hop/no-broadcast chat system).

Diagram 2 **(above) illustrates users on Node 1 communicating (zero-hop/no-broadcast chat system).

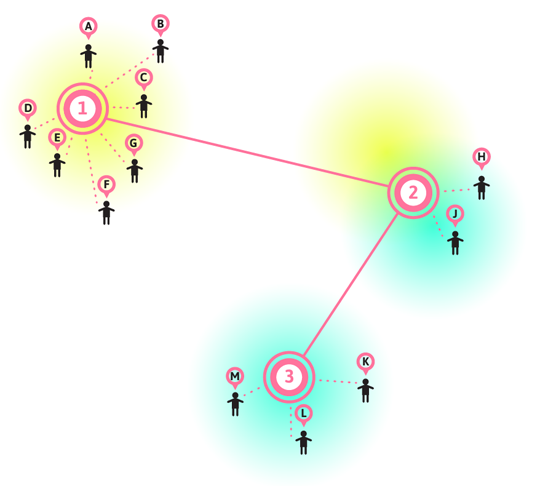

**Diagram 3 (above) illustrates a next-neighbor broadcast chat system, in which nodes would broadcast all messages to nodes within a one-hop distance. This system would allow a person to chat with people connected to their own node or their next neighbors, but not nodes two or more hops away. In Diagram 3, Person G can chat with Person C because they are both connected to Node 1. But in this stage Person G can also chat with Person J because J is connected to G’s next neighbor, Node 2. Person G could not chat with Person L though, because Node 3, which Person L is connected to, is two hops away.

**Diagram 3 (above) illustrates a next-neighbor broadcast chat system, in which nodes would broadcast all messages to nodes within a one-hop distance. This system would allow a person to chat with people connected to their own node or their next neighbors, but not nodes two or more hops away. In Diagram 3, Person G can chat with Person C because they are both connected to Node 1. But in this stage Person G can also chat with Person J because J is connected to G’s next neighbor, Node 2. Person G could not chat with Person L though, because Node 3, which Person L is connected to, is two hops away.

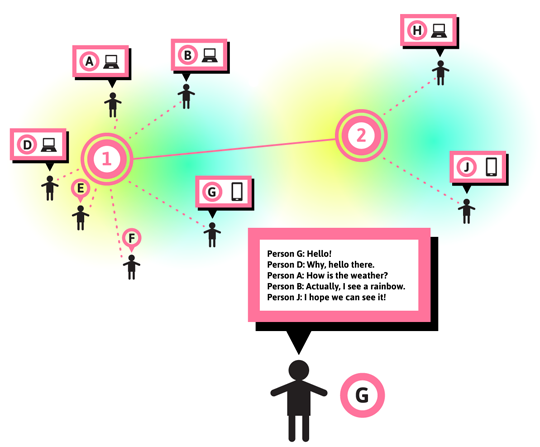

Diagram 4 (above) shows the next-neighbor broadcast chat system, illustrating users on Node 1 communicating with each other and users on Node 2.

We hope that these diagrams can help spur conversations about decentralized application development. Stay tuned for more meshages.

Diagram 4 (above) shows the next-neighbor broadcast chat system, illustrating users on Node 1 communicating with each other and users on Node 2.

We hope that these diagrams can help spur conversations about decentralized application development. Stay tuned for more meshages.